|

Phillips High

School |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Baptist and Methodist churches were long ago razed. The Jolly Drug, Ostrum's Grocery, 66 Theater and 66 Cleaners, all of the stores. Gone. Look hard enough and it's possible find a few foundations where the company-owned homes once were. Even the streets are long gone.

"It was a unique town," said Tommy Birch. "Just different in the best of ways."

The exceptional school, which got the best of the best, is the only thing still standing, but few can tell what it once was. The classrooms have been converted into office space. The football field, home to one of the Panhandle's football powers, is used for storage.

Phillips, Texas, once had a magical ring to it. Now it's a ghost town, a memory of what was and what will never be again. The spirit of that "Leave it to Beaver" town comes to life once a year from its graduates, who are the only physical link to what for many was the time of their lives.

"Oh, I loved it," said Louise Gunter of Amarillo. "It was so friendly. It was like one big, happy family."

Gunter, 86, is a graduate of the Class of 1940. Her three sons are Phillips graduates. She was part of the organizing committee of the first official Phillips homecoming weekend in 1952, and she hasn't missed one in 57 years.

"We had to pass the hat to get enough money to send out postcards to everyone," she said, "but we've had one ever since."

For 34 years, homecoming was the same as at any school during the fall. But when the town left on flatbed trailers in the mid-1980s, it was moved to the second weekend in July. This past weekend, there was a golf tournament and gatherings in Borger and Lake Meredith, and at the heritage center in Stinnett.

"This is important to most of the exes," Birch said, "especially to those who were there when the school spirit was really high."

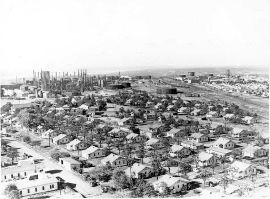

The town, just two miles northeast of Borger, came to be in 1927 with the construction of the Phillips Petroleum plant. The high school graduated its first class in 1936, two years before townsfolk voted to name the town after the company. It was a company town in every sense.

Unless a man was a merchant or taught school, he worked at the Phillips refinery. Men walked to work with hard hats and lunch pails. Kids knew when the school day was about over when they heard the shift whistle blow. Every August marked the Phillips Free Fair.

The company owned and paid for almost all of the utilities in the cookie-cutter houses. With few exceptions, the frame houses were almost all the same.

"We were like a peerless society," Birch said. "When you went to someone's house you'd never been to before, you didn't have to ask where the bathroom was. You knew. Everyone in Phillips had the same income except for the supervisors. Their houses had basements. They were like mansions to us."

The company insisted on the best in its school. The taxes to the school district made sure nothing was lacking. Birch, who graduated in 1961, said 20 of the 60 boys became engineers. Some of his early college classes in math and chemistry seemed to be a repeat of what he had at Phillips.

Chesty Walker's football teams from 1939 to 1956 were legendary. His teams were 172-23-8. They won six regional crowns at a time when that was as far as teams could go. The 1954 team went 15-0 and won the 2A (now 3A) state title.

The Blackhawks were strong through the 1960s. The 1967 team advanced to the semifinals, where, in an ironic twist of two ships passing in the night, Phillips met Plano, now a Dallas suburb of 275,000. The late Mark Hatley, Green Bay Packers vice president of operations, was a member of that team.

It was more than just football. Olympian Jill Rankin Schneider, considered the area's top women's basketball player, led Phillips to the 1976 state title. The marching band would rival the football team. The Phillips band played in the 1960 and 1967 Cotton Bowl parades, and Gunter remembers going to Bartlesville, Okla., headquarters of Phillips Petroleum, to play at Frank Phillips' 66th birthday in 1939.

But Shangri-La can't last forever. Society and business changed. Things began to wane in the late 1970s. The company began to offer money to residents to move to expand the plant. An explosion in 1980 seemed to hasten things.

The residents' final stand was in 1985 when Phillips Petroleum and M&M Cattle Co. sent eviction notices. Residents tried to negotiate with M&M, but Phillips bought them out, making it official. The last of 470 houses had to be gone by Dec. 31, 1986. The last graduating class was 1987.

For those exes who watched houses leave on flatbed trailers for neighboring towns, it was a gradual process. For those who left and came back for homecoming, it was too much. Birch said initially some didn't want to see what had happened to their hometown.

But as they realize every July, they took the stores, churches, homes and people out of Phillips long ago, but taking Phillips out of the people, that's almost impossible.

Jon Mark Beilue's column appears Sunday, Wednesday and Friday. He can be reached at jon.beilue@amarillo.com or 806-345-3318. His blog appears on amarillo.com.

|

All email addresses have @ replaced with _AT_ to discourage spam. Webpage

updated: 13 July 2009 |